Firstly, hello to our few WordPress subscribers. Hope you enjoy getting email notifications of Wanstead Climate Action’s occasional blog posts. Some of you we know, and some we don’t. Just to be clear, we don’t get around to putting very much on the blog at the moment, and instead our regular communication is via a monthly email newsletter (currently using MailChimp). Please do sign up to this via https://wansteadclimateaction.com/sign-up/ The newsletter generally focusses on matters local to Wanstead and Redbridge, such as our repair cafés or pollinator pathways, but wherever you are in the world, you’d be welcome to join.

The fact that we imagine most of our 500+ email subscribers are more interested in the small, local things doesn’t mean our core group isn’t interested in ‘thinking globally’ and in national and international campaigns. That’s really how WCA started, and groups of us still often travel together to London for demonstrations, which this September include a Stop Rosebank event, Stop Trump march, and Make Them Pay.

It’s the spectrum of possible climate actions that this surprisingly wordy bonus blog is concerned with: from mass street mobilisations at one end to weeding the street at the other. The tension between ‘individual’ and ‘systemic’ action, and between local and global focus, are recurrent, if often unarticulated, questions within environmental groups and the climate movement as a whole.

Solitary summer solstice soliloquy

The subject occurred to me back in June as I made my way from the Saturday morning Wanstead Flats Parkrun to the WCA stall at WREN wildlife weekend in Wanstead Park, and decided to do a litter pick while walking the kilometre between. I don’t bring gloves or sacks to Parkrun, so the task usually requires finding a discarded plastic bag or two that has blown into the broom bushes and then bending over to fill it with cans, glass and bits of (micro)plastic. (One one occasion, the polythene bag that was available was huge, presumably used for packaging a fridge freezer or other white good, and attempting to use its entire capacity, the amount of rubbish became nearly too heavy to drag to a waste bin without injury.)

So this raised questions about whether the litter pick (a kind of ‘direct action’) was a more effective use of my time than spending time on the stall, helping collect names for a local petition or having potential conversations about a Fossil Fuel Treaty or the effects of international supply chains on human rights – the second option being a kind of ‘political action’, hoping to influence human social systems. And while doing some kind of informal environmental cost-benefit analysis just for the litter pick, is it worth separating out valuable recyclable aluminium and glass and just junking the plastic which is supposedly very inefficiently recycled and even adds to more plastic supply and ultimately litter? More specifically still, is the contribution to microplastic dangers from a few grams of expanded polystyrene packaging and cladding in any way significant given the biggest contributor to microplastics in the environment is wear from car tyres? As pointed out in a previous blog, he sheer size of the gap in scale between individual action and the global problem is both daunting and hard to grasp, and so may discourage even thinking about it.

To be sure, there is also a social aspect to the effect of the litter pick; it’s about more than the physical amount of rubbish removed. Studies show that people drop more litter where there is already accumulated human debris, and the fact that people are seen to be caring for their local environment may boost the sense of community and local collective action. I know other people who volunteer at Parkrun and take on more regular and comprehensive litter picks near Bush Wood, while Wanstead also boasts two monthly collective litter picks, one in Wanstead Park organised by FOWP (Friends of Wanstead Parklands), and one around the village greens involving local councillors (see Wanstead Village Directory for details). Then there is the Redbridge Goodgym group, and Wanstead Community Gardeners, all looking after the local area in additional to professional street cleansing and forest rangers, because there’s still a lot of waste discarded and blown around after a picnic.

And you can see local estate agents’ interest in this kind of local improvement of the visual environment. I can’t avoid thinking litter-picking is kind of petty compared to the enormous issues of social and environmental justice around the world. Yet for me it links back to the standards and ethics I grew up with, with parents perhaps tutting over those who left litter and me learning that the public environment beyond the family was something to care about. Further, while a discarded crisp packet may provide nesting material to a bird or shelter to a snail, it’s a warning that humans can be careless about impacts on other organisms in ways that are not always so visible.

Plastic is a big deal – but is it a symptom?

How many people make any connection between litter and the climate and nature crisis? As I filled my plastic bags on the way to and through the Park, what came to mind was a kind of challenge posed by an acquaintance (call him Michael) that Boyan Slat has done far more good for the environment than Greta Thunberg. I didn’t think it worth the time to respond then. Now, readers (hoping you are still here) should know of Greta if they’ve not been living completely off-grid in Epping Forest for the last decade, and how as a teenager she confronted world leaders with the physical urgency of rapidly declining budgets and the alarming numbers that accompany them, and how world leaders seemed to forget again under the hypnotic influence of money, but they may not recall Boyan Slat. Slat is a young man who developed schemes to clear the gyres in the ocean of plastic waste, such as cleaning up the ‘Great Pacific Garbage Patch’. It’s a practical action addressing some of the distressing imagery broadcast in David Attenborough’s ‘Blue Planet II’ TV series. It’s also a temptation to think that a technological solution can undo some of the harms we’ve done to our vast planetary host, and sometimes maybe it can. At that age, some decades ago, I was wondering if it were possible to remove heavy metals and other pollutants from the environment using some kind of electrolysis. Of course, scooping up large amounts of water and air for some kind of filtering process can simultaneously harm the organisms that live in their medium, but maybe there’s a balance. Is there some case that the proposed direct engineering solution, retrospective but well-intentioned, might be as significant as cutting pollution at source? My friend Michael was dismissing my praise of Ms Thunberg not to be contentious for the sake of it, but from a deep suspicion of one kind of popular environmentalism; he’d apparently swallowed the (possibly deliberately engineered) idea that ‘green’ was a new religion competing with his own Christianity, effectively the idea that Greta and climate experts were some kind of ‘false prophet’.

Here’s the thing. The marine clean-up schemes, some worthy of academic investigation, did receive significant media coverage, if minor compared to Greta’s tour of international conferences and the school strikes. But the amount of physical material the schemes address, even if they somehow captured all the plastic near the ocean surface, is of the order of one millionth of the global carbon problem. Carbon dioxide emissions are around 40 billion tonnes per year, while plastic production has been around 500 million tonnes – so if you can compare them, plastic represents little more than 1% of the fossil fuel use. And what happens to that plastic at the end of its useful life? Less than half is incinerated (19%) and half is stored (not always permanently) in landfill, while only about 1% is released to rivers and the environment. (One of Mike Berners-Lee’s many pie charts shows 0.5% ‘leaked into oceans’, 1.2% into rivers and lakes; 7% is ‘open air burning’ which tells an unpleasant story [A Climate of Truth, 2025].) And the vast majority of that either falls to the bottom of rivers and seas or is beached, literally littoral litter. That 1% of 1% of 1% of fossil carbon leaves an unpleasant but rather diffuse collection of plastic bottles, beer-rings and (mostly) fishing gear near the surface jeopardising epipelagic organisms. The ocean gyres are massive areas and would be very energy-intensive to sweep up. It is a commendable and innovative idea to do an ocean litter pick, but really not dealing with the problem anywhere near the source and more of symbolic value for the (micro)plastic issue; whereas demanding restrictions be placed on fossil methane production would reduce the need to market the plastics in the first place. I am sure the school strikes have in fact, almost accidentally, done more to counter the ocean garbage patches, and in fact plastic litter beyond our own suburban areas, than attempts to clean up the most visible signs of plastic pollution.

Dealing with denial, doubt and disagreement

Here’s the other thing. The contentious distrust, dismissal and disapproval expressed towards young people calling for some kind of system change, whether winding up the fossil fuel industry or some economic measures, may have been a form of classic psychological denial of some suspected half-knowledge, or it may have been a genuine lack of understanding of the scale of the environmental problems caused by changing chemistry of ocean and atmosphere – but it still suggests Michael was thinking in terms of some kind of responsibility towards the natural world. The notion of ‘stewardship’ may be too ‘anthropocentric’ for some green philosophies, but one can see most religions and philosophies motivate people to care for the non-human world: both on a small scale acting kindly for animal welfare, and more dramatically Christian Climate Action hanging banners in and from cathedrals at the weekend.

Michael’s and my values might be similar, and it appears we disagree on priorities just because we disagree on facts, which is why I point to some facts above. However, as psychologists and sociologists find, understanding facts divides people less on climate than tribal and political allegiances, perceived moral norms and media exposure – you don’t really need to understand atmospheric physics to think when 99% of experts are indicating a problem that there’s no smoke without something burning that shouldn’t be. It’s no wonder though that most climate-concerned people react to the ‘whataboutery’ objections and naysaying with annoyance, and try to respond with whatever information is to hand; these objections are not just dismissive, but turning your own sincere environmental or social concerns against you and casting doubt when action is urgent.

Another example might be the belief, engendered partly by the film Planet of the Humans and almost as popular among ‘eco-primitivists’ and doomists as deniers, that PV panels use more energy and material to produce than the carbon they save; easily disproved with a little reading. What about the landfill waste from wind turbine blades? Well, big strides have been made in recovering and recycling blade material, and what about landfill waste in general? And of course the hypocrisy card: how can you protest when your clothes are made of petroleum-based plastic, or you cut down trees and make things from them? These can be, unless deconstructed, very successful ‘climate discourses of delay’, dissuading people from climate action unless they feel their personal life is perfect, and generally making what can be really very straightforward (the need to shut down fossil fuels) into some apparently complex trade-offs that mean you apparently need expert knowledge even to speak about. I remember asking internet wisdom, many years ago, detailed questions about the real value of green electricity supplies and and whether landfill gas in fuel mix could be considered sustainable. One response was both kind and frustrating, along the lines of ‘I don’t know, but it’s great that you care’. One could genuinely care about ocean plastic litter, but caring is not enough if you don’t get try to get some realistic sense of what might be the most effective actions. Dr Jane Goodall said ‘Only when our clever brain and our human heart work together in harmony can we achieve our true potential.’

The personal is political – and ecological?

So it would help to recognise all of the obstacles arrayed against really making human activity sustainable, including the economic and ideological power of corporations that filters down through numerous PR companies into media and political discourse and everyday conversations. Politics is a dirty obstacle to climate action, but also (sadly perhaps) an essential part of the solution. And yet words are not enough either unless they actually preserve and restore habitats, prevent chemicals leaking into the environment, and stop disturbance to the carbon cycle and other planetary boundaries. Showing a good example and how it makes you feel, while acknowledging that no one is perfect, is another way of changing unwritten norms besides the necessary changes to regulation and monetary values, and yet it needs to be on a much bigger scale than litter-picking or planting a few trees. Paul Powlesland, local hero and leading light in both the River Roding Trust and Extinction-Rebellion-aligned Lawyers for Nature, summed all this up in the Guardian in 2022:

“I’ve come to see the importance of cycling between the micro and the macro. … If I just work in Barking it’s irrelevant because these trees will get drowned by climate change. Litter picking is a perfect example. It’s a tsunami of single-use packaging and it feels like trying to wipe off the overflow from the bath rather than turning off the tap, and for packaging we really need to turn off the tap. On the other hand, the local helps keep your sanity and keep you motivated.”

(It also demonstrates to yourself that you care for where you live, that bit of Earth for which you can show stewardship.For Paul Powlesland the River Roding is sacred and his explanation when doing jury service that ‘nature is my God’ might almost give credence to Michael’s opposition of earthly concerns to what he considers sacred himself. But that’s a story for another time. There’s also a movement for rivers not just to be given rights but for people to marry them – we may have a local showing of ‘Rave On for the Avon’ soon.)

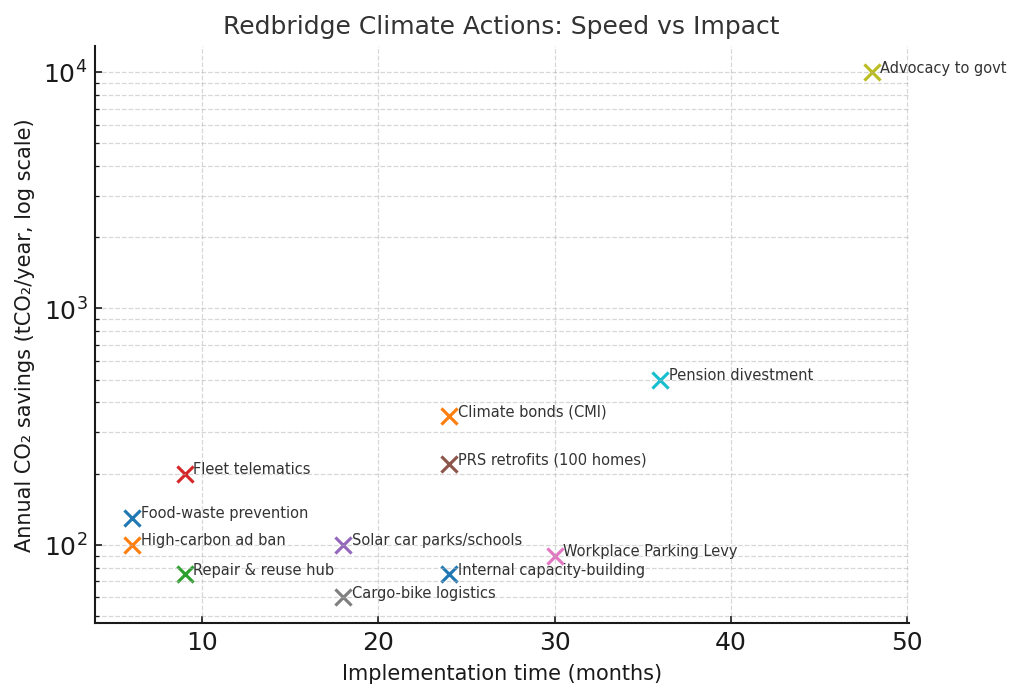

So some kind of balance between practical, direct action and political campaigning, where neither is to the exclusion of the other, for both the individual and the organisation seems healthy. And this balance of actions and words would also apply at levels bigger than individuals and communities, at local authority, national and international level. An interviewee in the documentary ‘The Race is On’ describes ‘polycentric governance’ that recognises each level of self-regulation and action from the micro to the macro. The political-practical distinction does seem to be an issue at local level in Redbridge council’s draft climate plan for 2025-2030: there are actions aiming at bringing council operations to zero carbon by 2030, and others using what influence a local authority has to reduce residents’ transport and heating emissions over a timescale that one would hope is not actually much longer. What it omits is a third element of advocacy and co-operation with outside bodies, to accelerate national policy for housing efficiency improvements and plan for a fair transition to a fossil-free future. In trying to respond to the draft, I have to admit I did take the suggestion to use AI, specifically to find relevant actions in FoE/Ashden council case studies that could make a difference. ChatGPT really ‘tries’ to appear helpful and after being asked about advocacy as an action it volunteered various policies Redbridge could lead London councils on and the diagram above. Note the log scale on the vertical axis – and also that the AIs disagreed among themselves about scale of potential savings, but all three I used suggested that indirect financial and political effects exceeded the proposed rate of PV deployment on public buildings by at least an order of magnitude, with one outputting ‘Advocacy effects are harder to quantify, but even small nudges at central policy level dwarf local project impacts’. Reasonable point.

Mike Berners-Lee, this time in How Bad are Bananas? (2020 edition, p194), shows a diagram of two overlapping circles marked ‘cut my carbon’ and ‘push for change’:

Cutting our individual carbon footprint is essential, but the other ways we can push for change are even more powerful. … Even though none of us are going to be able to show how we single-handedly transformed the whole world, we can become part of a movement, the power of which is far more than the sum of its parts. And that’s enough.

Well, we have to actively hope it will be enough, and that people can find part of their time to be responsible to the biosphere as well as their responsibilities to family, work, property and community. Unlike most of the diagrams in the book, the relative size of the two circles may not be based on careful research of hours spent. How do you measure ‘importance’? In kilograms of carbon saved per hour’s work? That probably varies a lot between individuals – well-off residents probably have both more scope and more agency to cut their environmental impacts, while people in private rented accommodation are perhaps better using their time more on campaigning, for changes they cannot effect themselves.

Wellhead and tailpipe

Besides local/global, and direct/political, let’s note that there is a third important dimension in the context of effectiveness of climate action, alluded to by Paul Powlesland. This is the ‘supply’ and ‘demand’ distinction from economics, the difference that George Marshall summarised as ‘wellhead’ carbon extraction versus ‘tailpipe’ carbon emissions. Which is more effective and important lever, stopping new oil, or insulating Britain? Hopefully we can cover this in a forthcoming book-review blog and newsletter. Here though are a few observations for now. ‘Supply’ and ‘demand’ here really refer to the same physical activity: digging up fossil carbon and adding it to atmosphere and ocean, but they denote a split between different notional agents, organisations and groups. So intuitively wellhead and tailpipe might bear roughly equal responsibility, with reductions required in each driving the other. Indeed it turns out the choice to approve a new gas or oil field has some partial ‘rebounds’, in that if you prevent 100 million tonnes of carbon being drilled in one place, another operator may well be induced to dig up 50 million tonnes more elsewhere (a 40-50% factor incidentally that means even considering inefficiencies of shipping methane via LNG containers, new North Sea gas fields would considerably add to global emissions).

So is the same true of ‘rebounds’ in ‘demand’? If you stop heat loss your flat by amount X, do you use X amount less energy, or do you also enjoy the warmth from being insulated? If you save money, do you spend it on flying abroad? Does the gas company lower prices infinitesimally and sell more gas to another resident, or to a plastics manufacturer? I would like to think the rebound here is also intuitively 50%, but at least one of those Mike Berners-Lee books worryingly mentions that the rebound can be over 100%: an increase in efficiency or renewables on its own might actually increase consumption and pollution.

Conclusion and action

Please don’t let the complexity of these potential trade-offs put you off. Just remember that all the top climate actions are necessary but not sufficient. It’s horses for courses, and a choice which we work on, and within Wanstead Climate Action you see the local, national and international (a trip to COP26); the direct (repair cafe, litter picks) and indirect (campaigning for warm homes and a big climate plan); the demand (opposing SUVs, solar on car parks) and supply (divesting the council pension scheme, getting the City to rule out insuring fossil projects that would push us beyond tipping points).

This blog may hold a record for most mentions of Mike Berners-Lee. On which subject, maybe every blog about environment should end with a suggested action, and hopefully someone has made it this far without unsubscribing from the blog (and some people have also subscribed to our separate newsletter). Action: Mike Berners-Lee is chairing a National Emergency Briefing in Westminster with seven other experts on climate impacts and solutions, on the morning of Thursday 27 November 2025. It’s an important opportunity to actually ensure debate and policy are based on evidence rather than on corporate lobbying and media myths. Please check if your MP is going, and if not email them. Thank you.

Comments are left open for introductions, questions and thoughts.

Blog by CK. Not necessarily the view of WCA.