Merchants of Doubt by Naomi Oreskes & Erik M Conway.

(and The Burning Question by Mike Berners-Lee and Duncan Clark.)

It’s a political thriller and an eye-opening story of high-stakes skulduggery, and the villains are high-profile physicists – and it’s all true.

Two books came to mind when thinking about what to do for our first monthly book review to sync with the WCA newsletter. I read the two back-to-back over ten years ago; both are highly readable and both have glowing front-cover reviews from Al Gore (alongside long explanatory subtitles); and both get to the nub of the climate problem, albeit in different ways. Together, they give a clear indication where climate-concerned people (maybe anyone who cares about anything) could most effectively concentrate efforts. One is this exposé of the public relations tactics used to pull the wool over the public’s eyes and stall progress – whether on smoking, acid rain, pesticides or global warming – and particularly a history of how and why certain scientists were willingly co-opted into these deceptions. The other, The Burning Question (2013) by Mike Berners-Lee and Duncan Clark, I should rule out for a full review because it is sadly currently only available in epub format, but I’d like to give a few comments on it here anyway. After all, it’s ‘hugely important’ (Dr Jim Hansen); gives an even bigger picture and supportive background to the other book; and motivated some people to spend years working on ‘climate’, a term that depending on your standpoint is a woolly concept subsuming all environmental concerns, or a euphemism for shutting down fossil fuels as fast as possible.

The subtitle of the second book poses the uncomfortable burning question: ‘We can’t burn half the world’s oil, coal and gas. So how do we quit?’ Since at latest the 1992 Rio conference, we’ve supposedly been trying to ‘quit’ or give up the habit. (It helps to return to the smoking analogy again and again, just as the Merchants of Doubt cover shows a cigarette as a chimney.) However, energy use and emissions have continued on the same exponential upward trajectory (exponential in a literal mathematical sense, doubling every 39 years) – so what went wrong? Both books give convincing answers and therefore present challenges that the human race desperately needs to overcome.

If we’re addicted, what’s responsible?

In The Burning Question, the earlier book’s public relations story, which we will come to, plus the hundreds of millions of dollars used to influence (or corrupt) US elections and candidates, is included under the appropriate heading of ‘sabotage’. But that is alongside many other considerations about fossil-fuel ‘lock-in’: failures of international negotiations (again largely sabotage); how one energy source opens up another rather than displacing it; how efficiency gains can cause ‘rebounds’ and greater consumption elsewhere (neither demand-side reductions nor renewables are enough on their own); reluctance to write down energy and transport investments; ideological framings like ‘GDP growth’ and energy security; psychological resistance to confronting the problem head-on; and to be frank, a continuing lack of appreciation of the realistic and urgent perspectives presented in this book. Most of these factors are accompanied by supporting data, charts and useful references, largely compiled by Clark, a data journalist at the Guardian. The book isn’t perfect, for example, in an effort to explore every hypothetically viable pathway to sustainability, it gives too much time and credence to industrial and agricultural schemes to store carbon as proposed get-outs. For the most part though it consciously avoids the many common distractions from the central issue and provides any campaigner with the basic knowledge to start and respond in climate conversations and take action.

The Burning Question had that unique position of concentrating almost entirely on the fundamental fossil CO₂ conundrum in detail (apart from short sections on deforestation, soil and fertilisers), but Mike Berners-Lee has also incorporated summaries of the conclusions of The Burning Question into his two later books, There Is No Planet B (2019), where it forms the 14-point appendix, and A Climate of Truth (2025). That is perhaps one reason why TBQ hasn’t been reprinted, and small parts of its perceptive analysis might be considered outdated since its discussion of temperature targets anticipated the Paris Agreement, and the language of international negotiations has since changed.

From tailpipe to wellhead

Fortunately another part of the text is still freely accessible, since the foreword by Bill McKibben, (presented in the book under a non-clickbait title for those who have already bought the book: ‘Do the Maths’) is available on the Rolling Stone website (2012). I could make the case made for this article being the most important writing ever about climate, and therefore about anything at all. If the climate movement is fractured or introspective or getting lost, as it is again in 2025, re-reading it should jolt us out of complacency.

Until we understand the framing of the article, ‘three simple numbers … that make clear who the real enemy is’, we might think of fossil fuels as an unsustainable resource that also happens to cause pollution and climate change, and perhaps even worry about ‘peak oil’ and future energy price shocks and the need to reduce consumption. All that was a misleading perspective. Instead, the article suggests we choose a viable temperature target and how confident we want to be in avoiding it, calculate a carbon budget using current science, and see how it compares to available fossil reserves. In the case back in 2012, these are a 75% chance of avoiding 2 °C, a 565 Gigatons carbon budget, and a ‘terrifying’ 2,795 Gigatons, so we knew of five times more more coal, oil and gas in rock than we can extract.1 We’ve not got a shortage of carbon ‘resources’ as previously sometimes thought, we’ve far too much.

The three numbers I’ve described … provide intellectual clarity about the greatest challenge humans have ever faced. We know how much we can burn, and we know who’s planning to burn more. … the more carefully you do the math, the more thoroughly you realize that this is, at bottom, a moral issue; we have met the enemy and they is Shell.

Sic. This last point apparently refers to Walt Kelly’s poster and cartoon for the first Earth Day in 1970. Partly because the picture speaks a thousand words that might be criticised as a simplistic overemphasis on personal responsibility, but mostly for copyright reasons, I won’t show it in this blog. It shows the cartoon character Pogo collecting scraps of litter into a sack, disheartened and overwhelmed by the sheer amount of junk littering a forest floor, with the caption ‘We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us’. Maybe such a message helps us take collective responsibility, including being conscious of the powerless and vulnerable. However, surely we have to believe that humanity can change so as to coexist with the rest of Earth’s biosphere, and in that case we need to pinpoint how: what exactly are the things that need to change?

Something is rotten in the state of power

Both books and the article were published after the 2008 financial crisis but before the 2015 Paris Agreement. It seemed clear to the authors then that an effective climate agreement would have to practically halve the value of fossil fuel shares, since they are priced on fossil assets that cannot be burned under a global climate regime. But the stock markets barely seemed to notice Paris, and to this day continue to irrationally underprice risk in the way they did the systemic risks associated with subprime mortgages. Reading this now, it’s obvious something is seriously broken in the system. It’s as if big finance believes that governments are not serious and that people and planet will lose for the sake of maintaining shareholder value. The WCA book club has not covered either of these two books, but in one we did, Climate Crisis and the Green New Deal, economist Robert Pollin explains that fossil fuel investments have now fallen to 5% of global equities, so if they were wiped out completely, it wouldn’t be the end of the world. Unfortunately, if this carbon bubble doesn’t burst soon, it quite possibly will.

So with The Burning Question briefly covered, we’re at the half-way point in understanding how fossil-fuelled corporate ‘superorganisms’ (a term that goes much wider than the legal fiction of the corporation, including beliefs and behaviours throughout society) are extraordinarily evil, described as ‘psychopaths’ by Prof Joel Bakan. Presumably in order to function, individual humans who work or invest in these institutions don’t realise exactly how evil. How can that be? The Burning Question confirms that availability and promotion of fossil fuels are the big push factor in the climate crisis – it’s not that energy demand and individual choice are irrelevant, but capping or limiting extraction is essential. At the risk of disappearing even further into abstraction here, the power systems that have survived to shape society and allocate resources are those that can command internal loyalty and defend themselves and their reputation by whatever technique, by using ‘ideological power’, which is largely a set of social beliefs and allegiances; if an entity can convert its economic resources into a suitable ideological frame it can maintain its structure and processes, whether that’s producing drugs or messages. Humans who are either cynical or politically aware would suspect large corporations use PR to distort truth to their advantage and cannot be trusted, but what we need are case studies to show the actual dynamics involved, and this is where our top-billed book comes in.

Groundbreaking, but not digging for coal

Merchants of Doubt must have been highly influential over the last 15 years, judging from the number of references to it and the stories it tells. Not only was there a feature documentary of the same name, but you can see its themes elaborated in the three-part BBC/PBS series Big Oil v The World, the first series of BBC Radio 4’s How They Made Us Doubt Everything, several subsequent books and investigations and even a Royal Shakespeare Company play.

When I first read it, MoD put much context on my experiences from 2004 onwards encountering climate misinformation online and in news stories: typically someone online would claim global warming isn’t happening, it’s happening but it’s natural, and it’s happening because of humans but it’s good, often all three ‘beliefs’ at the same time. Most people don’t have time to check the dozens of doubts and distortions about climate science, but I feel like I’ve now encountered and investigated the lot (and often sadly found that the situation is worse than either I or the contrarians initially believed). I can assure anyone reading this that unless we’re living in the Matrix and there’s a vast conspiracy to fake both electromagnetic spectra and the history of science since the 1850s, global heating from increased CO₂ is a real, definite thing and threatens the stability of many Earth systems. When I traced back the credibility of the sources that made the climate problem seem less certain or serious than I’d read in science books, the majority were ‘think tanks’ with names like ‘Competitive Enterprise Institute’ or ‘Heritage Foundation’, and a handy Greenpeace website (ExxonSecrets) showed they were all funded by oil companies (which do more to hide their tracks nowadays).

Merchants of Doubt, by two historians of science, isn’t quite the comprehensive guide to fossil-funded front groups that I remember it as, but it details much of these organisations’ political evolution from their attacks on the 1980s ‘nuclear winter’ hypothesis and support of Reagan’s ‘strategic defence initiative’ (SDI, ‘Star Wars’) through to opposing tobacco regulation – it’s much the same institutions and individuals that have been countering inconvenient truths for decades. Subsequent books and media have filled in gaps about the ideological misinformation ‘junk tanks’ (as George Monbiot calls them), including the ExxonKnew revelations (2015) now prompting legal action in the US. Among the books, our book group has read The New Climate War by Michael Mann, and Don’t Even Think About It by George Marshall, but there are also good investigations free online by the likes of Desmog, Sourcewatch and Powerbase and Naomi Oreskes continues to engage with investigating and exposing the PR efforts alongside other academics like Geoffrey Supran and Robert Brulle.

In fact only one of the seven chapters (plus the introduction, which you can read online for a flavour of the narrative style) is really about climate change; the others cover smoking, SDI, acid rain, ozone, passive smoking and pesticides. The world has made substantial progress on smoking and acid rain, and CFCs have been almost totally eliminated, but delaying climate action is still of course a very live issue, because we have no reason to suppose the most powerful of the industries involved has stopped lying just because the public conversation has largely moved on from doubt about the problem to manufactured doubt about solutions. All the same, one benefit of a historical perspective is that it shows how things work in general, in this case how ideology and industry tends to shape public perception of science. The long view can cast light on current events, and also show things go back further than you might expect. For example, rereading the book reveals that what I wrote above about Bill McKibben making it clear in 2012 that we have far too much fossil fuel, not too little, has a precedent, in that energy guru Alvin Weinberg was saying that in the 1970s (p 181). And showing the immense power of public relations to reverse progress has itself a longer pedigree than in this book: Alex Carey’s research collected in Taking the Risk out of Democracy showed how business groups were doing this kind of manipulation from the 1910s, radically changing both mass and elite opinion about consumer protection and worker’s rights, and, as with the events concerning science and scientists, leaving a trail of suspicion and social dysfunction.

Oreskes’ other works also look at how the practice of ‘pure’ science, while in theory aiming to approach objective knowledge, is shaped in its interests and pursuits and publications by external direction, typically from industry and military. Marketing arguably made the modern world: you can see the influence of fossil companies trying to expand their market from Shell’s touring road maps to the concrete infrastructure around us, so in some ways it is not so surprising that science, and some individual scientists, fell into line.

A wisp of doubt

The first case study, the prototype, concerns how industry reacted to knowledge that smoking causes cancer. Being British, I associate the important science with epidemiologist Prof Richard Doll in the 1950s, but he is not even name-checked here, since there was laboratory evidence of tobacco being a carcinogen as far back as the 1920s (all the same, still a century after the basic ideas of evolution and the greenhouse effect). Yet there was still public ‘debate’ and denial about smoking’s health effects until the early 1970s, with many lives and families sacrificed to tobacco profits. The point here is that doubt was the fundamental strategy, applied across all these cases (coincidentally mostly different forms of air pollution). They didn’t really want or need to convince people that smoking didn’t cause cancer. They just had to try to frame it as a scientific ‘debate’ to paralyse regulatory action and bog down individual behaviour change, mired in the claim that more research was needed and it was premature to act.

The overall PR aim is sometimes called ‘FUD’ (fear, uncertainty and doubt), while the specific tactic of recruiting respectable-sounding scientists to muddy the waters is called a ‘white coat strategy’, or simply the ‘Tobacco strategy‘. This is where the first of the human villains enters: Fred Seitz, a physicist who had worked on the Manhattan Project and been president of the US National Academy of Sciences, who is now given a role reporting to the board of tobacco company RJ Reynolds and disbursing over $45m in tobacco grants for medical research from the 70s onwards. Why? Because the research is concentrating on every cause of cancer other than cigarettes. Much of the science produced useful results, and yet it was spun to both the grassroots and the elite in a successful attempt to confuse and distract. The corporations needed some control of related science. By the early 60s, the industry’s own research showed that tobacco was carcinogenic and addictive, but outwardly it pretended there was ‘no evidence’ or ‘proof’ of a causal link, and was trying to ‘keep the controversy alive’. Sound familiar?

A crucial point made here is that doubt really is part of the scientific process, with scientific papers couched in tentative language and with all the limitations listed. Moderate scepticism or an open mind can be rational. So it is possible and effective but unfair and dishonest to ‘weaponise’ or ‘leverage’ doubt for propaganda purposes. What isn’t really scientific is ‘debate’, even if it sounds reasonable to most people as a way to resolve a contested question. There’s a ‘passive smoking debate’ or a ‘climate change debate’ or a ‘heliocentrism debate’. There is no debate among the experts. What debate suppresses I believe is the curiosity that motivates discovery. ‘Debate’ substitutes a conclusion in place of a hypothesis in the search for evidence, and encourages irrational, disproportionate doubt. By also perverting journalistic standards of ‘balance’ into ‘false balance’, the tobacco companies could defend their primary product by producing something else that their 1969 strategy document described: “Doubt is our product since it is the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the minds of the general public.” Discernible overtones of relativism and ‘alternative facts’ there, and if you criticise the methods you may get irrationally accused of inhibiting ‘free speech’. The reasons for the book’s title should now be clear.

(A widely-cited equivalent of the doubt memo to counter climate science is a 1998 American Petroleum Institute ‘action plan’ that aimed to measurably shift public attitudes towards ‘uncertainty’ – and if you compare coverage at the time to misconceived politicians’ statements now the basic goal seems to have been achieved. Following the explicit intention on the first page, to defeat ‘initiatives to thwart the threat of climate change’, a skewed narrative is presented where ‘environmental groups’ threaten the industry and their dissident position. Were the fictions in that narrative genuinely ‘believed’, or meant as a useful background story for their scientists and other spokespeople? Was the document partly the PR people selling their agnotological services to the oil companies? Was anyone involved remotely concerned with reality?)

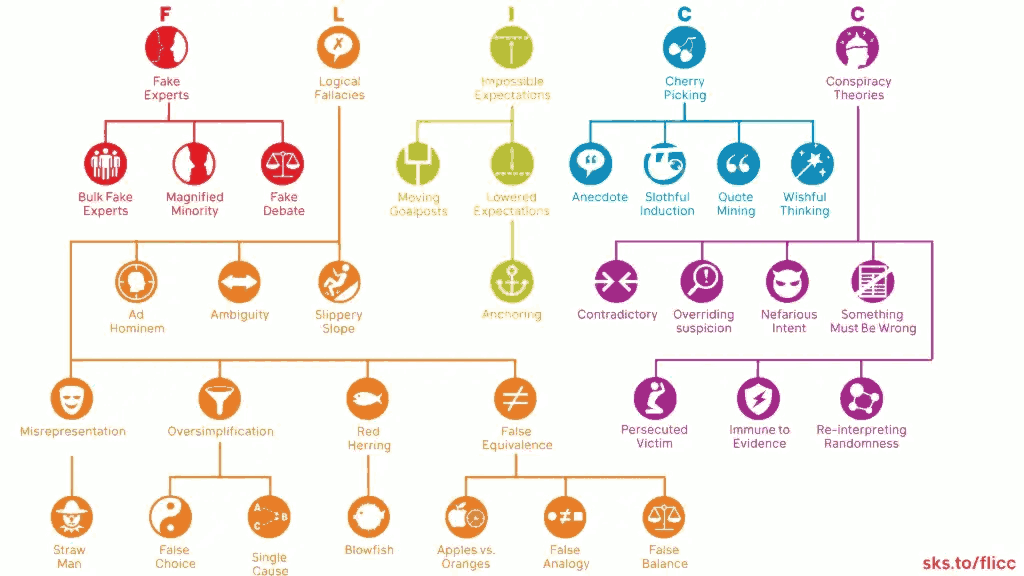

FLICC

Since the book’s publication, academics have categorised anti-science arguments or confusions common across areas ranging from anti-vaxxers to climate change doubt-mongering. A useful mnemonic is FLICC, which stands for: Fake experts (this retired astrophysicist disputes climate change without ever have published research on it); Logical fallacies (the climate changed in some ways before human civilisations existed, so human civilisations aren’t responsible for current changes and can’t be harmed by them); Impossible expectations (scientists can’t predict the weather 50 years in advance); Cherry-picking (one particular glacier is advancing, or it was warmer here last year, and my father lived to 110 despite smoking 60 a day); and Conspiracy theories (scientists are ‘scaremongering’ for the grant money or because they are linked to the World Economic Forum/UN/Bill Gates).

The fake experts are essentially where the book starts from: besides Fred Seitz, his three colleagues – who also attempted to undermine regulation of cigarettes, CFCs, nuclear weapons, pesticides, coal plants and fossil fuels generally – were Fred Singer, William Nierenberg and Robert Jastrow. (The last died about 2020, so don’t worry about libel.) Each had previously had a distinguished scientific career, but essentially their opinions on the subjects they were recruited to dispute were no more reliable scientifically than your average citizen, and in fact less. They had no scientific accountability for their actions or their widely-disseminated statements, and they could freely employ the other tactics like cherry-picking and indulge a superior, dismissive attitude. Those were the days when people respected scientists; nowadays probably anyone will do as a contrarian.

The global warming chapter covers several incidents, maybe of increasing drama as the fossil fuel industry puts the screws on harder. First was what followed the 1979 Charney Report that showed global warming, not then detected by science, was likely to pose serious problems in future. Two more assessments were commissioned, where scientists again expressed concerns, but the potential risks were downplayed by economists. Then there was a case where the four retired physicists reacted to James Hansen’s announcement to US Congress that global warming had been detected by misrepresenting the graphs he had presented, and claiming solar changes could be responsible for warming (they can’t), in association with one of the ‘think tanks’, the George C Marshall Institute (which had been set up around the nuclear debates in Chapter 2). Then things get really dirty and distressing.

Fred Singer had by this point apparently made a full-time business out of climate denial, and tries to co-author a paper minimising climate risks with one of the founders of modern climate science, oceanographer Roger Revelle, who was suffering with a heart condition in the last months of his life; this effort appears to be part of a strategy to undermine Al Gore’s candidacy for US vice-president, since Gore studied under Revelle and was threatening gentle climate actions like fuel efficiency standards. The attempt to extract a prominent deathbed recantation from Revelle led to Singer being widely criticised for misrepresenting Revelle’s views and Singer suing for libel. Very messy, but court cases sometimes reveal the tactics we’re interested in. The process of science is relatively open to historical research anyway, but insight into the ‘other side’ is more obscure and mostly opened up because of class action suits, libel cases, and general spats.

The next spat seemed particularly vicious, but strategically directed at an individual and their scientific contributions. An ‘ad hominem’ argument refers to not just strictly a logical fallacy predicated on a case that someone has been wrong before, it can also mean outright attack on your opponent; in addition to FLICC techniques, the big guns can orchestrate a major press campaign against someone’s personal integrity to the point of destroying their life. (It helps if you pre-emptively accuse your victim of what you are yourself guilty of, for example, editing and distorting text for political reasons.) By the time of the IPCC’s second assessment report (SAR) in 1995, it was already well-established that carbon dioxide was rising, that that would be expected to cause temperature to rise, and that temperature was rising. To be honest, that’s pretty convincing already for me, but there was the theoretical possibility that the rise was somehow smaller than expected and something else was contributing, like the solar effects that the junktanks were promoting. Unfortunately for them, Ben Santer conclusively demonstrated that atmospheric measurements showed the ‘fingerprint’ of greenhouse gases, not of the Sun. The stops were pulled out for Santer, with extensive nonsense allegations in finance rag Wall Street Journal, lawyer Don Pearlman (the villain in the RSC’s Kyoto) screaming in Santer’s face, and unprecedented letters of support to Santer from dozens of senior scientists, one of whom told Nierenberg ‘I have no desire to cooperate with anyone who endorses such an unmitigated collection of distortions and misinformation’. The WSJ still printed more of the fake allegations from the fake experts than the truth from the real ones. Odd, that. And ultimately the power of disinformation and lobbying was shown when the US Senate later refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol 97-0. Irrationality triumphed. Of course, the sums involved in promoting myths beneficial to industry is in the millions, a small fraction of corporate profits but far greater than raised for campaigning by democratic parties in the UK; even a propaganda campaign worth less than a million, if using calculated messages and trusted messengers, can have enormous ripples.

The equivalent attack on the IPCC’s third report in 2001, barely covered here, focussed on another conclusive bit of evidence, the ‘hockey stick’ showing no global heating similar to the 20th century for a thousand years. One of the targets here was Prof Michael Mann, who came out fighting with books and media appearances and in 2024 winning a libel case. Perhaps he is even energised by contact with the anti-science forces, but nothing satisfies them. After a cache of emails was leaked from the University of East Anglia Climatic Research Unit (CRU), Mann’s colleague Prof Phil Jones became a focus of attacks just for doing his job as a scientist (with even George Monbiot caught up in the hysteria), and despite being cleared by eight different inquiries, cruel and ignorant allegations rumbled on online for years. The kicker in ‘The Trick’, the drama starring Jason Watkins as Jones, is that the allegations all over the press designed to undermine climate action were self-contradictory nonsense to start with. Recently, Dr Santer, who himself back in 1997 realised that the same scientists who had attacked climate fingerprinting had been employed indirectly by tobacco companies to attack the Environmental Protection Agency, and who is now perhaps freer to talk in relative retirement, gave his opinion on the importance of climate research and the use of Trump to censor it and decimate its funding.

Ad hominem vs ad institutionem

I described Merchants of Doubt as an exposé, but it is also scholarly in a way that allow you to draw your own conclusions before the authors’ own. The authors tend to focus on understanding the role of individual scientists, whereas I’m more interested in the larger corrupting systems of corporate propaganda. I would generally accept the conclusion that what motivated Singer, Seitz and the others, was not just the money and prestige of a non-research role, but probably their personal and ideological investment in Cold War notions of secrecy and technological advance, and after the Cold War ended their quest for something else that threatened their worldview, settling on the case for environmental regulations as the new foe (anti-communism is the most polarising of Chomsky’s five filters). Likewise, the working scientists were largely a mirror image, characterised by collegiate modesty, most interested in pursuit of truth among those who understand their field rather than the utter ‘garbage’ going on in the press that they believe must ultimately cede to reality and rationality. But of course, the group of scientists backed by industry money are given more sway with public, media and decision-makers, than are the quiet researchers who are ‘chilled’ and risk attack from the same influences.

The conclusion about the broader mechanisms behind science denial also seems supported and consistent. For a while, I believed it was a matter of chance that right-wing parties had become more susceptible to climate disinformation – there’s nothing inherently anti-environment about either left or right, and perhaps it was just a vicious circle where the Republicans got more fossil funding, adopted policies beneficial to polluters, and so attracted even more funding. Admittedly, it does go a long way back, with Jimmy Carter installing solar panels on the White House roof, and Ronald Reagan ripping them off again. But what the misinforming ‘junk tanks’ share is an ideological commitment to ‘free markets’ to the point of rejecting regulations that would benefit the general public, and that currently corresponds to a significant factor in the political ‘right’. And no politican’s discourse, nor my views nor anyone else’s, has gone untouched by this vast, genuine conspiracy to misinform the public; if we realise the extent of it, we could try to compensate or be extra diligent in checking basic research, but at the risk of increased doubt and tensions and wasting time.

A corollary of all this, hinted at in How They Made Us Doubt Everything, is that not only has industry undermined public trust in the integrity of specific science that is inconvenient to their interests, but in expertise and factual claims in general. Surely, we should at least agree on the fundamentals of objective reality, even if we disagree about whose interests are most important in dealing with that reality. But that is breaking down now, with impatience and suspicion that challenging views are merely a form of manipulation affecting ‘both sides’ of any manufactured ‘debate’. There’s sometimes a feeling we have nothing in common. Does FLICC represent habits of thoughts that can be more subtle than outright conspiracy thinking? I’m thinking of a Wanstead figure who says they hold to Karl Popper’s falsificationism – in a simple form where nothing is ever proved true, only false; this person also states a belief that Michelle Obama is a man. Something has gone wrong with epistemology when arguments from authority become inverted and a random nugget on the web (possibly originally in jest like QAnon) sparks so much doubt it forms a whole narrative. Is the amount of motivated misinformation a threat, as the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists suggests? Probably.

Ultimately this book explains why there has been ‘doubt’ about climate change despite its certain and pressing threat, but it may have a greater value in proposing how to think about science for society and what a healthy scepticism is. Perhaps it can even help in how to identify and defend oneself against propaganda and conspiracy theories and filter out disinformation. Rather than debate, they propose thinking more about balance of evidence, and investing more in science communication.

Two classic analyses, several possible strategies

So what can be done to tame, shrink and eliminate the literally inhuman monsters that are behind plastic, land, air, and water pollution, poisoning the carbon cycle, and threatening life on Earth? Is it conceivable we can convince some of the senior humans that support this system to somehow disassemble it from the inside? Shareholders want their dividends and want to postpone the crash while they’re still in control, so it seems unlikely that cancers in society can be neatly excised when they are valued in billions. What seems more hopeful is the McKibben idea of targetting of those shareholders, largely institutional pension funds (like Redbridge’s) – which can survive the transition without any significant losses simply by investing in less destructive enterprises. Similarly, Insure our Future aims to convince the insurance companies that fossil projects need services from, but which are also systemically threatened by the longer-term effect of such projects.

The Oreskes and Conway book only goes as far as to suggest spreading awareness of how perception of knowledge can be gamed, but you could also use it to define another ‘pillar’ supporting the polluters: public relations, lobbying and advertising. There are campaigns explaining to workers in these sectors what a moral position would look like, and how to go fossil-free. Another approach to preserve a sane sense of reality would be regulation, effectively banning expenditure on influencing public or political opinion by fossil interests – given that it’s precisely this manufacturing of doubt that has delayed effective regulation of pollution of the environment, can it also delay regulation of the pollution of democracy?

For the better communication from research to decision-makers, ask your MP to attend the National Emergency Briefing on Thu 27 November.

Footnote

1 In 2018 the carbon budgets were loosened a bit, but if the 2023-4 surge in warming indicates greater climate sensitivity, then they may be tightened again. 50% chance of ‘2 °C’ is now around 1050 GtCO₂, less than a third of fossil reserves as reported in 2022; 50% is a massive gamble with mass extinction. For a thought-provoking UK calculator see Carbon Independent. Even ignoring climate tipping points or assuming we will keep within them, the cause of climate justice is that the rich should not profit at the expense of the lives and livelihoods of vulnerable people now or in the future. So we repeat that every fraction of a degree counts, not every 0.1 °C or even hundredth of a degree, but every barrel of oil extracted. (In a footnote to this footnote, I notice that the 565 Gigatons carbon budget, and 2,795 Gt are the figures used in a famous, bleakly funny, scene in Aaron Sorkin’s Newsroom (2014). However, the use of the 2,795 Gt is not the same as in the Rolling Stone article, so it’s not as hopeless as in the fiction. Yet.)

Blog by CK. Not necessarily the view of WCA.

Coincidentally, the day after this review went live, YouTuber Simon Clark PhD published an hour-long video called ‘Should lying about climate change be illegal?‘, investigating online ‘AI slop’, and also suggesting a campaign in the EU to ban climate disinformation. At about 7 minutes in, Simon says

We’re proposing high-carbon advertising bans, but would also be interested in any campaign to restrict corporate PR – which is presumably most effective when not obviously an advertisement but going through front groups.

LikeLike